The Importance of Understanding Financial Literacy on Family Farms by Dr John Noah & Professor Teresa Hogan

Financial Literacy on Family Farms

With financial literacy being widely perceived as the solution to creating individual financial responsibility and contributing towards the stability of the economic system, there has been a significant increase in research measuring personal financial literacy across the world with studies generally finding widespread low levels along with significant heterogeneity within populations.

Surprisingly, there has been much less attention on financial literacy in micro and small enterprises (MSEs). In an Irish study,1 81% of owner managers stated that financial literacy was important, however only 46% thought they had a good level of financial literacy. Owner-managers were reluctant to address this weakness for a variety of reasons including a lack of time, the cost of training, inappropriate methods of training or believing it was not their responsibility but rather their accountant’s. These findings, and the lack of research in comparison to personal financial literacy, suggest there is still a lot learn about financial literacy in MSEs.

Our research focused on understanding financial literacy in micro and small family farming enterprises. Ireland’s agricultural industry plays a significant role in our economy with 137,500 farms, of which 99.7% are classified as family farms, and it accounts for 7.1% of total employment. Family farms are currently at an important inflection point as a combination of factors shape the future of farming, including the new Common Agricultural Policy in 2023, sectoral emission targets as part of the Government’s Climate Action Plan, and instability in global supply chains leading to significant input cost inflation.

All these factors create a challenging financial landscape for Irish family farms, particularly in the context that 27% of Irish farming households are economically vulnerable while another 31% are only economically sustainable due to the presence of off-farm income.2

With such significant changes on the horizon, the coming months and years will be crucial for these farms (and families) as important decisions regarding the sustainability of the current farming system will be made. Such decisions inevitably involve a significant financial component and farmers will need to be supported to make the right decisions.

Research has shown that accountants are one of the most used and trusted advisors to farmers and, consequently, they will have a key role in guiding farmers through this decision-making process. Understanding the relevant costs and benefits, not only in the short term but over a longer-term horizon for the farm will be important as will understanding how to effectively present this into a meaningful analysis that is understandable by both the farmer and the broader family unit. This is where accountants should thrive given their skillset and experience of undertaking such financial analysis.

In understanding financial literacy at a farm level, our research moved away from viewing it as a binary concept – implying that someone is either financially literate or illiterate – and sought to explore how financial literacy revealed itself on different farms through the financial practices that farmers engaged in.

The perception of farmers as hating the “bookwork” and the stereotype of the biscuit tin full of receipts being given to the accountant just before the tax deadline each year oversimplifies a complex issue of how farmers and their families engage with financial information at a farm level and what influences these practices, which was the core focus of our research.

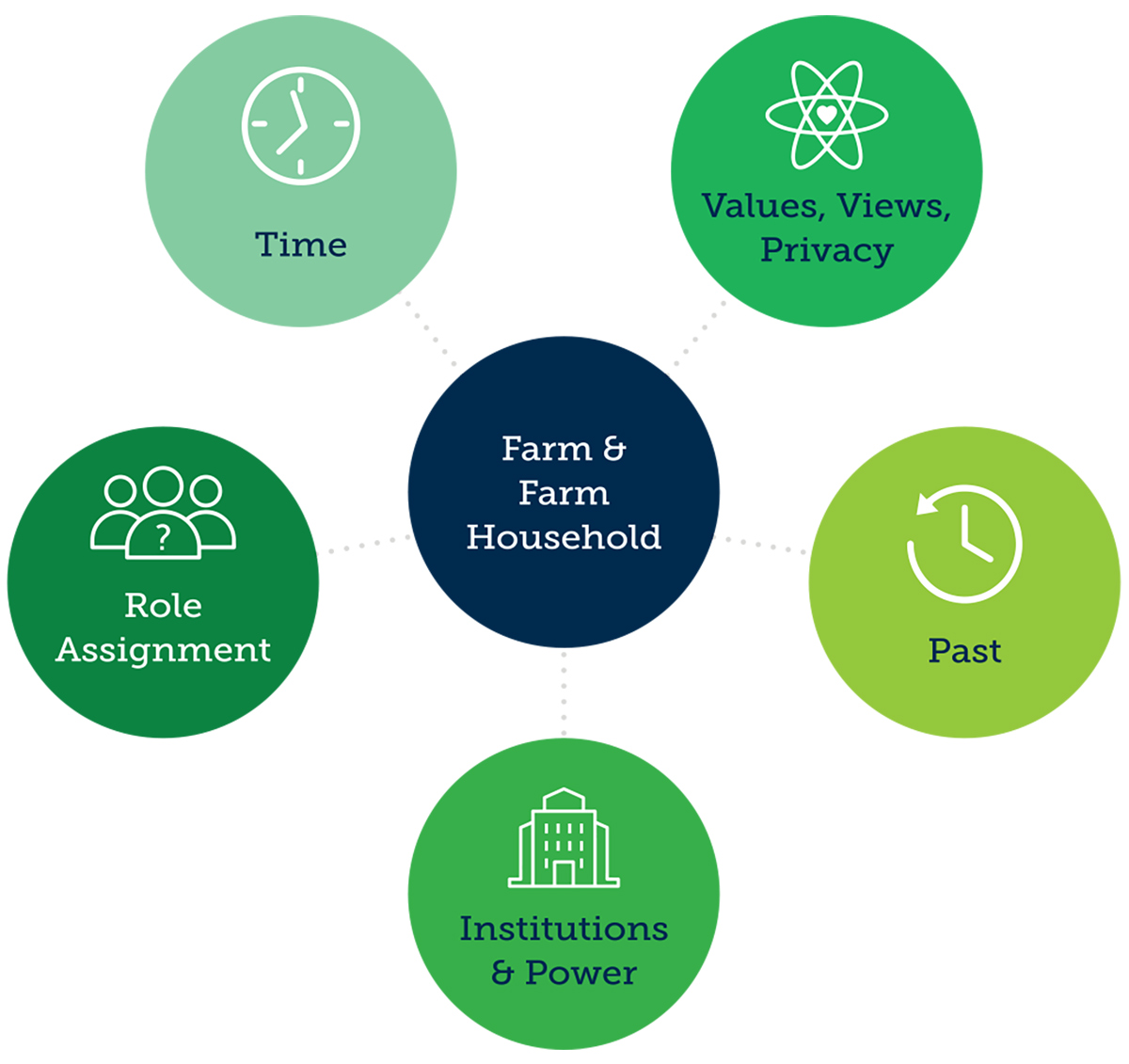

We identified a number of important factors when examining financial literacy at a farm level which can provide important insights for accountants that are engaging with family farms.

The financial practices of the farmers are centred around their management of time across the farming season. The farmers constantly balance their time between various tasks on the farm at different times of the year. This results in the farmers making trade-offs between time spent on financial related tasks and time spent elsewhere on the farm, depending on which tasks the farmer perceives to be more important or of value to the farm.

The routine each farmer has with respect to financial practices on the farm is another important dimension as all the farmers in our study have particular times of the day and times of the year that they focus on financial related events on their farms. The annual financial cycle on the farm with its repetitive milestones (e.g. financial year end, tax deadlines, loan repayment dates) reinforces this focus on a financial routine and each year the farmers’ financial practices become more embedded.

This importance of time in understanding financial literacy on farms creates an important insight in terms of targeting key “engagement moments” on a farm when the financial side of the business has the farmer’s attention.

When a farmer does not identify the financial aspects of the farm to be central to their identity as a farmer (or they perceive them to be of less value than other tasks on the farm), they can often delegate many of these responsibilities to either other family members (e.g. spouse, son/daughter) or to external parties (e.g. bookkeeper, accountant). We find that spouses and children in the farm family play an important supporting, and sometimes primary, role in the financial related events on the farm.

This can often mean a disconnect arises between those that are managing the day-to-day financial records and tasks on the farm (e.g. managing invoices, cheque lodgements, collecting receipts) and the person making the financial decisions, which the farmer often retains responsibility for. Such a disconnect can create issues in terms of targeting education initiatives and advisor engagement given the split of responsibilities within the family unit.

This highlights the importance of viewing the farm from the family perspective and understanding the different roles undertaken by family members.

In our case study, the importance of the past in terms of tradition, inheritance of financial practices from previous generations and the farmer’s own previous financial experiences, combine with considerations for the future around the farm’s financial viability and the next generation to influence current financial practices. There was evidence of financial practices being inherited from previous generations and a sense of tradition in terms of how and when certain financial events and practices take place and who is involved. For example, the continued use of a traditional pen and paper approach – which the farmers would have learned from the previous generation – to the financial records on the farms studied is in contrast to the adoption of technology in other aspects of the farm to save time and labour (e.g. calving cameras, online herd registration apps).

Another influence on financial practices was the role of the farmers past financial experiences. Previous experiences of dealing with banks, financial pressure on the farm and the experience of farming in more difficult economic times all shape the farmers’ approach to their farm finances and associated practices.

These influences highlight the important role of history, of both the farm and the farmer, in understanding financial literacy on farms and the origin of the current financial practices.

Family farms operate in the context of significant institutional influence and our findings put a focus on the power relationships that exist between each farm and the various stakeholders in the farm financial ecosystem. Key deadlines set at an institutional level (e.g. DAFM scheme payments, tax deadlines, bank loan repayment dates) create temporal pressure on the farmers which drives much of their approach to financial literacy.

Certain financial texts (e.g. Teagasc eProfit Monitor, annual farm accounts) and associated practices would be seen as dominant financial literacies as they are driven by various stakeholders (e.g. banks, Revenue, Teagasc, DAFM) in the farm financial ecosystem and failure to master them can result in penalties for the farmer (e.g. breach of loan agreement, tax penalties) and disempowerment.

This institutional focus on dominant financial literacies contrasts with the farm level approach observed in our study whereby the farmers undertook more informal financial practices to understand the farm’s performance and financial position.

While cashflow budgets, breakeven analysis, and financial statements are standard terms to accountants, for many farmers they are often technical jargon that only serve to distance the farmers from the analysis and decision-making process as opposed to engaging them. Many farmers, over time, develop their own accounting system that works for them (local financial literacies – e.g. the “back of the envelope” calculation).

While these informal approaches may be much less visible to outside parties, as they are not supported at an institutional level and can be unique to each farmer, they play a very valuable role at a farm level to inform farmers’ decision making and should be an important consideration for advisors when engaging with farmers on financial matters.

The value that each farmer perceives coming from the financial side of the farm and how they view the role of farming are two key influences on the financial practices on the farm. Farmers that view farming as a way of life and a vocation with little focus on the financial performance of the farm tend to outsource much of the financial work on the farm to other family members (e.g. child or spouse) or an accountant which can result in a disconnect between the farmer and the underlying financial performance of the farm.

In contrast, those farmers who viewed the farm as a business that needs to generate a return financially, and who placed significant importance on the financial side of the business, proactively engaged with the timing and nature of financial practices on their farms. In our study, the perceived value of the financial performance of the farm and the farmer’s view of the purpose of farming were heavily influenced by the family structure (e.g. existence of dependent family members, household reliance on the farm income), the existence of a clear successor, and the level of farm debt which increases the financial pressure on the farm. Furthermore, the inherent closeness of the farm’s financial performance and the household’s own finances can create an issue of privacy and an aversion to discuss such issues in the public domain, which is in contrast to the tendency of the same farmers to be happy to discuss other aspects of farm performance in those same social settings.

This theme again reinforces the importance of context in understanding how farmers approach the financial side of their business.

- Small Firms Association, 2019, ‘Financial literacy amongst Irish micro, small and medium-sized businesses’

- https://www.teagasc.ie/publications/2022/teagasc-national-farm-survey-2021.php

Dr. John Nolan is an Assistant Professor in Accounting and Corporate Finance in University of Galway and completed his PhD on financial literacy in family farms in Dublin City University in collaboration with Teagasc.

Professor Teresa Hogan is Professor of Entrepreneurial Finance at DCU Business School. She is a member of the National Centre for Family Business, and her research interest is focused on SME financing, working capital, venture capital, and acquisitions.